There’s something about Leonardo

From science of the enigmatic to puzzling cinema

|

|

by Stefan Schmidl |

Ron Howard’s screen adaptation of Dan Brown’s bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code (2006) is likely to be considered as a temporary highlight of a long series of popular conspiracy and mystery movies dealing with art. However, the origins of this particular genre can be found partly in European turn of the century science. Initiated by the blueprint of biologist Ernst Haeckel’s The Riddle of the Universe (1899) there arose a big amount of publications around 1900 (especially by humanities) that used a strategy now common in popular mass media: to constitute alleged mysteries in works of art and to come up with a more or less original solution - or a conspiracy thesis.

One of the first studies of this kind was Viennese art historian Max Dvořák’s The Riddle of the brothers Van Eyck (1904), in which he synthesized the biographical mistiness surrounding the titular artists with questions of “mysteriously” evolving style patterns. Among many others scholars from all kinds of academic disciplines there would follow Erwin Panofsky’s discovery of a “disguised symbolism” in Early Netherlandish Painting (1953) much in this vein. It was a late echo of this school of thinking when Thomas Kuhn defined normal science as “puzzle solving” in his groundbreaking treatise The Structures of Scientific Revolutions (1962).

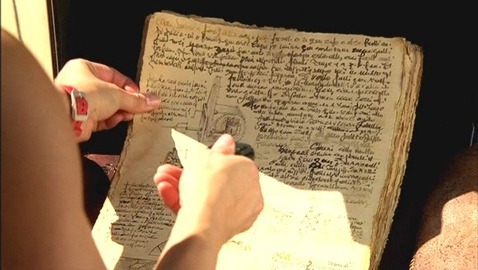

Certainly the most influential of all these scientific publications was a short essay by Sigmund Freud, Leonardo Da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood (1910). This psychoanalytical foray in revealing “secret messages” in Da Vinci’s art (it has to be remembered that it was not until 1952 that Charles de Tolnay presented the first comprehensive study on the Mona Lisa in art history) emerged as so successful with the audience that it was soon imitated by musicologist Max Graf in a short paper in which he tried to do the same with Richard Wagner as Freud did with Leonardo: finding reflections or sublimations of childhood traumata in an artist’s work. Two years later Swiss psychoanalyst Oskar Pfister joined this approach when he published an article on a would-be identification of a “hidden” vulture in Leonardo’s Madonna and Child with St Anne. This idea was actually incorporated into the second edition of Freud’s essay in 1919, serving here as a concrete substantiation of psychoanalytical art theory.

But this overall concept also fell on fertile ground in applied arts: In 1915 German composer Max von Schillings wrote an opera about the “mystic smile” of Leonardo’s most famous work, taking advantage of the public hysteria following the spectacular robbery of the Mona Lisa (1911) and presenting a purely fictional story of love and betrayal around the painting, complete with lurid music. Austrian writer Leo Perutz followed suit with the novel The Judas of Leonardo(1937-1957), which describes the creation of Leonardo’s Last Supper within a morality tale.

There is quite a simple idea behind such paradigms of interpretation: If it is exceptional, then there must be a secret behind it. As the works of Leonardo, Bosch, Gesualdo, Rembrandt or Bach actual went beyond the scope of their ages’ norms, they consequentially entailed a big bunch of exegetes from various backgrounds who tried to unravel the artists’ seemingly enigmatic pieces of art. With the advent of narrative film the model had to be watered down radically to meet the new medium’s demands. But the nucleus remained the same and conjoined well the trivial fascination with conspiracy theories and hidden hints.

In commercial movies pieces of art are generally shown as being in need of explanations in order to be fully comprehended. This formula may be a result of the lasting uncertainty that came with the avant-gardes of the 1920s and evoked insecurity among non-expert audiences. Since then public practises with contemporary art were problematic. But also to look at pre-19th century art was not the same any more. Therefore a high percentage of painter and composer biopics came up with details of artists’ life that should add to a really illuminative understanding of a certain artwork, but often remain purely voyeuristic or speculative. A fine example of this kind of approach is Bernard Rose’s Immortal Beloved (1994) which presents a letter Beethoven wrote to an unknown lover as linchpin of almost everything in the composer’s creative life. Various Rembrandt and Van Gogh movies work in a similar way.

Another aspect of art in film concerns deep layers in canvases, poetry or music. These sources of uncertainties (to adapt a classification by French sociologist Bruno Latour [1]) are predestined to hold puzzles; at least that is what screenwriters love to do. In this way they resemble human scientists of the first half of the 20th century who conducted their research similarly. Paul Schrader vested this image of hierarchic layers in a metaphor of a painting hidden behind a painting in Brian de Palma’s Obsession (1976).

Obsession (Brian de Palma 1976)

This idea is so popular that it even shows up in a routine thriller like John Badham’s Incognito (1997) in which a faux Rembrandt painting covers a secret portrait of the faker’s ill father, making it a quite blatant oedipal allegory.

The protagonist’s look at paintings in Rebecca (1939), Laura (1944) and Obsession is always also a look at the mystery of the particular female heroine. Sometimes this look becomes investigative and this way an active tool in the storyline - like in Vertigo (1958), where the fateful necklace in the portrait of Carlotta Valdes causes Scottie’s realisation of the deception he fell a victim to. Right there the representation of the enigmatic necessarily created an iconography of its own as well as corresponding patters in film music (in the form of Bernard Herrmann’s score).

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock 1958; Universal)

Time-worn as these paradigms have become, there were some refreshing exceptions recently: Although obviously modelled after Leonardo, Alias’ pseudo-Renaissance super-scientist Milo Rambaldi’s legacy functions more as a macguffin in the TV series than a separate topic of fictional art exegesis.

Alias(J. J. Abrams 2002; ABC)

In Alain Corneau’s Tous les matins du monde (1991) the music of French Baroque musician Sainte Colombe becomes the object of investigation for fellow composer Marin Marais. In the end he has to accept subjectivism as the essential drive behind all creative life. Coming up with such a clever idea tears this movie apart from comparable, more conventional celluloid biographies like Farinelli (1994) or Le roi danse (2000, about another Baroque master, Jean-Baptiste Lully).

Last but not least Umberto Eco’s novel Foucault’s pendulum (1988) has to be mentioned as a unrivalled parody of both ineradicable conspiracy theories and the methodology of projecting factitious puzzles into art. Taking it seriously, The Da Vinci Code nevertheless illustrated it nicely.

The Da Vinci Code (Ron Howard 2006; Columbia Pictures)

Marcel Duchamp’s attempt in liberating art and art theory from auratic thinking succeeded well with the establishment of conceptual art. But it never had any chance in commercial filmmaking. So be prepared for the next “biggest cover-up in human history”, but keep in mind what Freud remarked in the introduction of his Leonardo-study: “And, above all, the artist should not be held responsible for what subsequently happens to his works.” [2]