This text has been submitted as an original contribution to cinetext on August 5, 2003. It is also available as PDF-document for high quality printing.

Simulation Reloaded

|

|

by Seyda Ozturk |

In a recent interview[1] Jean Baudrillard states that the Wachowski Brothers had misapplied his theory of simulacra and simulation in The Matrix, as they embody the idea of the virtual as a concrete reality and carry it over to “visible phantasms”. What Baudrillard opposes to in the application of the distinction between real and virtual in the Matrix series is that “the brand-new problem of the simulation is mistaken with the very classic problem of the illusion, already mentioned by Plato”.

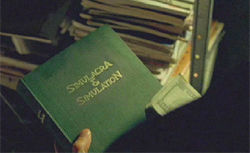

The infamous ‘desert of the real’ quote and the hollowed out book “Simulation and Simulacra” used by Neo as a box for keeping his illegal software (the simulation Bible becoming simulacrum itself) were apparent references to Baudrillard alongside other musings on the nature of simulation functioning as the main plot of the narrative. The structural similarity to Plato’s allegory of the cave also supported the simulation theme, in that Neo’s awakening from virtuality was unequivocally the moment of stepping out of the cave to meet the reality outside. However, reality Neo sees after being awakened from his evil dream was not the ultimate truth or the Real where truths are lit and perceived via the Sun, the source of the Good and the Just, but he was welcome in the Desert of the Real. Before moving on to the Desert of the Real and the notion of simulation by Baudrillard, it would be worthwhile to mention the Platonic connection with simulation in the history of the theory of representation, the problem of illusion and the status of the simulacra in contemporary reality. The main point of reference for such a theorization would not be Baudrillard, but Deleuze, whose writings on simulacra and representation open, according to Brian Massumi[2], a new way for dealing with our simulacral world while destroying the copy model distinction still dominant in Western thinking.

The Matrix (Village Roadshow/Warner, 1999).

When Deleuze, via Nietzsche, defines the task of philosophy as overturning Platonism, he proposes an eradication of the Platonic theory of essences and Ideas and its replacement by a theory of difference and becoming. Deleuze does this by extracting the category of the false from Plato’s theory of the Same and the Similar and by making this marginalized category, the simulacrum, rise and affirm its rights among icons and copies.

In Plato and the Simulacrum (Deleuze, 1990), Deleuze traces the advance of theory of representation and the status of copies and images therein from Plato onwards. Plato distinguishes between copy and simulacrum in his texts dealing with the method of division (the Phaedrus, the Statesman, and the Sophist) which is applied in the theory of Ideas in order to distinguish the thing from its images. Plato sets up a hierarchy of images, starting with the original represented by the good copy, which is good as of its intrinsic relation to the Idea of the model. At the bottom line of the hierarchy is the phantasm, the simulacra, which should be exiled as it possesses an extrinsic resemblance to the model but a very different dynamic of its own.

A simulacrum is an image that does not resemble; the image is maintained whereas the resemblance is lost. It does not have an internal relationship to a model but only an external relationship built on the “model of the Other (l’Autre) from which there flows an internalized dissemblance.” (Deleuze 1990:258) The illusory simulacrum escapes the authority of the idea and intimidates both models and copies; it is based on difference and is thus distinguished as a bad copy.

The Platonic model of philosophy is the Same and the Platonic copy is the Similar, in which simulacra with their differential points of view are to be turned into the Similar. Deleuze sums up the aim of Platonism as “to impose a limit on this becoming, to order it according to the same, to render it similar — and, for that part which remains rebellious, to repress it as deeply as possible, to shut it up in a cavern at the bottom of the Ocean” (Deleuze 1990:258). Overturning of Platonism can then be achieved by affirming the rights of simulacra among icons and copies. Deleuze assigns simulacra an affirmative and productive status: By denying the primacy of an original over the copy, one can explore the dimensions of an unreasonable and limitless becoming.

In his praiseworthy essay “Did You Ever Eat Tasty Wheat: Baudrillard and The Matrix”, William Merrin states that The Matrix, while playing with simulacrum, “domesticates it again beneath a higher and true reality: not once does Neo consider whether this "real world" he is shown might not be just another level of virtual reality -- perhaps this "reality" is one created for the machines by another intelligence to keep the machines themselves in happy slavery?” (Merrin, 2003) Preventing the overflow into madness that the resonance of the simulacrum generates, the narrative of the film depends ultimately upon a real that must exist. The ultimate dependence upon a real is the weak point of both The Matrix and Baudrillard’s theory of simulation and simulacra. In his 2001 essay “To Play with Phantoms: Jean Baudrillard and the Evil Demon of the Simulacrum” Merrin traces the development of the theory of simulation in Baudrillard’s writings and sketches the shift from a definition of the simulacrum as a semiotic conception that includes a “process of transforming the lived symbolic into its semiotic image whose reality-effect eclipses the former” (Merrin 2001:91) to a re-conceptualization that includes an establishment of a symbolic functioning as a critical foundation against the simulacrum. This attempt, Merrin states, is doomed to fail as the simulacrum rises and affirms itself against all efforts to domesticate it.

The power of the simulacrum that proves to be greater than that of the real is also central to Deleuze’s meditations on the simulacrum, where he links it with the Nietzschean notion of the Eternal Return. The simulacrum involves the power of the false, the power of producing an effect by way of reversing the icons and subverting the world of representation. This is achieved in the simulation of the Same and the Similar by way of which the Same happens again and again but each time with the exclusion of that which assumes the Same and the Similar. It is not a mechanical or habitual repetition, but one which extracts the manifest content “in order to reach the latent content situated a thousand feet below (the cave behind every cave...)” (Deleuze 1990:264)

The Real/The Virtual

When the makers of the Matrix movies signify the possibility of other simulations behind the VR in the sequel film, they overturn the very dichotomies of real/virtual, essence/appearance they represented in the first movie. They can be said to be replacing the Platonism of The Matrix with its very questioning and the brand mark motto of the first film “What is the Matrix?” with a new brand question “What is Real?”

The “What is Real?” question was, although only slightly implied, also a valid one for the first film both on a trivial level (Where shall the cyber rebels live once they defeat the AI, now that the surface of the Earth is destroyed?) and on a more sophisticated level (How can one define reality without simulacrum?). As Neo, the alienated and depressive hacker who uses Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation as a box for keeping his illegal software, was awakened from his evil dream and introduced to the Desert of The Real by Morpheus, many applauded and celebrated the introduction of the ancient idea that reality as we take it to be may in fact be a simulation to the masses via the delicacies and supremacies of the seventh art. What made The Matrix stand apart from other movies that deal with simulation,( e.g. Blade Runner, 13th Floor, etc.) was its encompassing the idea of all human kind enslaved in a simulation with great mastery on both a technical level (without doubt with the aid of its impossible-to-imitate techniques and special effects) and a philosophical level. (After all, it is the movie on the website of which is a section named Philosophy and The Matrix , and on which there have been published (until now) three books dealing with the now hip term “The Matrix and Philosophy”.)

The Matrix (Village Roadshow/Warner, 1999).

The sequel film seems to introduce a turn precisely at this point of reference to the real. Starting with Plato and carrying on with Baudrillard’s Desert of the Real, the narrative’s journey in the world of simulation has ended in The Matrix where Neo, after realizing his powers in the virtual as the chosen one, had “arrived at a totality of subjectivity – a whole – a hyperreal entity, more real than real.” (Gargett 2001 )[3] This hyper-reality is forced to question his new identity and whether what he was told is the truth in the sequel. One of the main devices for revelation in The Matrix narrative is the power of the spoken word. Neo learns about the virtuality of his reality from Morpheus, who in turn has believed in the One prophesized by the Oracle. The only way of escape from the Matrix is via an analogue phone, via the human voice. The power of the word is used to make one believe what she is expected to believe, language and signs become mechanisms of control. Whereas the first film has a linear narrative for setting up a dichotomy of real and virtual, the sequel introduces the theme of free will and control related to the war against the simulacrum. It becomes clear that the omnipresent simulacrum sustains and makes use of the long lost model to generate new simulations and to control the subjects within it.

The clear-cut distinction between real and virtual also becomes undermined by the detonation of establishing features of the narrative: one prophecy, one saviour, one reality become all dispersed into possible becomings in reality where only affirmation endures. The Architect at the core of the Matrix reveals that the Matrix is the sixth in a series and that Neo, accordingly, is the sixth One; a device for upgrading the virtual program into a more stable version where chances of deterioration are to be lessened in a new start.

Taking the remnants of human memory as its model, the Matrix exercises the practice of simulation by repeating this model in a positive movement of becoming. There is no more the opposition of copy and model, but a copy that has developed an inner dynamic of its own, a cyclical movement of repeating itself by manipulating its energy sources with the use of language. When the Matrix repeats itself, it does so by returning eternally a la Nietzsche. It does not repeat itself literally; instead, a different singularity emerges each time. As the ‘pseudo-Freud’, the Architect, explains towards the end of the sequel “The matrix is older than you know. I prefer counting from the emergence of one integral anomaly to the emergence of the next, in which case this is the sixth version.” The Matrix reproduces reality with each recreation, but not with the aim of affirming the power of Becoming over Being. It is in the quest for its own static Being which will finally erase the possibility of the emergence of anomalies. This production of reality is achieved via the powers of the false: a false prophet, a false underground city, a false one all joining for the recreation of the false. The power of the false knows, according to Deleuze, “how to transform itself, to metamorphose itself according to the forces it encounters, and which forms a constantly larger force with them, always increasing the power to live, always opening new "possibilities." ...There is will to power on both sides, but the latter is nothing more than will-to-dominate in the exhausted becoming of life, while the former is artistic will, or "virtue which gives," the creation of new possibilities, in the outpouring becoming....” (Deleuze quoted in Rodowick, 1997:140)

The Matrix Reloaded (Village Roadshow/Warner, 2003).

The Matrix opens new possibilities with each recreation, but not with an artistic will to power but rather with a will-to-domination.

The Movie Matrix as the Simulacrum of Simulation

Following Merrin, The Matrix is a Hollywood blockbuster that needs truths to deliver and the conclusion of the narrative with a loop of simulation in the third movie would be an over expectation. The film will probably be concluded with the establishment of this or that reality coherent enough to be comprehended by fans. Such readings will endure in the area of pop-philosophy and entertainment, but a precise application of the notion of simulacra in relation to The Matrix is not to be sought in its all-encompassing plot but in the status the movie has come to claim in our daily reality.

The notion of simulation has a twofold function in the Matrix series. It is not only the plot that introduces the notion of simulation, it is also the structuring and bringing to life processes of the Matrix phenomenon that function as a big, postmodern simulation. Dan Friedman aptly observes that the filmmakers are well aware of the fact that they are in fact only critiquing a real world which now comes to rely on a massive amount of simulacra and that their “simulation of simulacra” is part of the whole movie-making business. As a simulation questioning the new reality that consists of a multitude of simulacra, The Matrix continuously quotes from, besides a wide range of science fiction films, epistemological and metaphysical ideas, Christian imagery, Buddhism, etc. But the filmmakers cannot be blamed for cinematic plagiarism. The Matrix series repeat other science fiction films dealing with the notion of virtuality and simulation, they recreate Manga and anime films, transform Kung-Fu to Wire-Fu, they mix all the genres of film spiced with lines of thought to produce the perfect effect of simulation the seventh art is to achieve.

It is not only the moviemakers’ reflecting upon the film’s own production process in the movie but also the The Matrix mania that has come to express itself in new and productive ways which can lead to a discussion of a Deleuzian performance of simulation. The Matrix series surely touch the unknown centers of the spectators by playing with the fantasy that our dire reality may indeed be a simulation; but the reality we yearn for is not to be fought for as the possibility of its ever having existed cannot be questioned. What can be done is putting an end to the elegy for a lost reality by affirming and recreating our subject selves and will-to-artistic-creation.

It does not come as a surprise when we see the videos of hundreds of Japanese fans enacting a Matrix performance by dressing up like Neo, Trinity and Agent Smith and expressing their love for the movie. What they indeed express is the appraisal of the representation of our fantasies on the screen, as Tobias C. van Veen asserts:

“[B]astard offspring of The Matrix would be a crowd of queer Agent Smiths staging massive blow-ins on opening night . . . Of their own: of their own lives, not of someone else's Matrix fantasies . . . In other words: bring the thematic of The Matrix to the limit—escape The Matrix: fuck with it, make it something else—abuse the tele-networks—& shift from the reproduction of capital to the positive production of desire.”

As a pop entertainment creating the effect of the simulacrum perfectly with both its narrative and its marketing, The Matrix and the Matrix mania represent the power of the simulacrum; reality becomes simulacra. Just like Baudrillard's name will be forgotten whereas the notion of simulacra persists, so too will The Matrix be soon eclipsed by, besides other movies quoting from it and expanding its theme, enactments of subjects making The Matrix something else.

In “To Play with Phantoms”, Merrin writes that Baudrillard “recalls asking a Japanese interviewer why he no longer heard about his work in Japan:

and he told me, ‘But it is very simple, very simple you know. Simulation and the simulacrum have been realised. You were quite right: the world has become yours . . . and so we no longer have any need of you. You have disappeared’. (Baudrillard 1996c: 7)” (Merrin 2001: 104)

As Baudrillard states in the interview: “The system, the virtual, The Matrix, everything may go back to the scrap heap of History. Reversibility, challenge, seduction are indestructible.”