This text has been submitted as an original contribution to cinetext on Mai 9, 2004.

Being There with The King of Comedy: Television Seen From the Other Direction

|

|

by Robert Castle |

Television’s forward moving, all embracing, all consuming, emotionally reductive, seemingly irresistible ethos is neatly personified by Chance the Gardner/Chauncey Gardiner (Peter Sellers) in the film Being There (1979). Despite having little contact with the world for fifty years and being slightly mentally retarded, Chance mesmerizes everyone—realtors, politicians, newspeople, talkshow hosts—by virtue of his personal formlessness. Not full of sound and fury, his knowledge of the world is a tale told to him through the “idiot box. ” However, the film’s director and writer, Hal Ashby and Jerzy Kosinski respectively, do not make him a social “product” of too much television watching. Recall the scene in the Indian’s home in Natural Born Killers when the words “too much TV” appear across Mickey and Mallory’s heads but the mirror image of the television. Chance is television plus the qualities that television brings to the world. Chance knows nothing and knows no boundaries. He resembles Faulkner’s idiot, Benjy Compson. Benjy could switch consciousness of people and time with the sound of a single world (like a golfer calling for his caddie); the unpredictably mutable consciousness has been exteriorized for Chance into channel surfing. Ben (Melvyn Douglas) tells him at one point: “Ah, Chauncey, you have the gift of being natural. ”The logical extension of a boundless self—if we consider the absence of consciousness and ego “natural”—becomes, in movies, Mickey and Mallory Knox, who are divorced from their actions, sociopathic, whence point of view/perspective is surrendered to synthetic sophistication (Mallory’s poetry) and phony insight (Mickey’s lecturing television audiences).

It’s impossible to argue with Chauncey just as you can’t argue with television. One reason is that he sort of makes sense in the broadest fashion; secondly, if you suspect he doesn’t make sense, he still appears harmless if not a little funny, so why fight him. If you do confront or defy him, Chauncey will sap your will. For example, Ben’s doctor (Richard Dysart) reveals to Chauncey that he knows his real name, Chance, and has seemingly revealed the idiot for what he is. Chauncey remains oblivious to the doctor’s words and continues to speak about Ben, who is about to die. All the doctor can do is say: “I understand,” keywords signifying Chauncey’s own understanding without really understanding. The precise kind of un-understanding and ersatz apprehension of the world is the very thing that television perpetuates among most of its viewers. Television mesmerizes us into a feeling of understanding when very little is understood (knowledge without depth)—what we understand we have had little real stake in and thus aren’t bothered by the shallowness of this state of mind. The beauty of Being There’s satire lies in the strategy of depicting both television and its effects in a single man, whose personality absorbs friend and foe, combines idiocy and wisdom. All who meet him compromise their identities to accommodate themselves to him (not always done consciously). Likewise, the American public accommodates itself to the television/entertainment ethos; the process appears so innocuous that we have made the accommodation with few second thoughts.

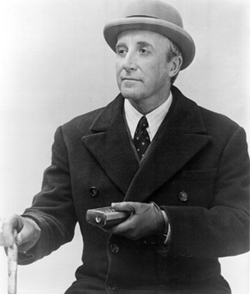

Chauncey watching television. Being There (Lorimar/UA, 1979).

The ultimate horror of Being There comes at Ben’s funeral. The President (Jack Warden) reads the eulogy and the political kingmakers handling Ben’s coffin are discussing the next choice for President. Chauncey’s name becomes the supreme choice because he has no past to hurt him and his ideas appeal to the television electorate. Politics’ infection from television receives such a splendid critique: the implication of his candidacy is that television itself will run for president! In other words (this is twenty-three years ago!), politics like sports has become a product of the medium. Joe McGinniss’ 1969 book, The Selling of the President, heralded this development while the film derived from it, The Candidate (1972) captures the growing emptiness of politics.

After Chauncey actually appears on a late night talk show, the public receives him with great adulation as a fresh new voice. A public yearning for something fresh. Sounding fresh, at least. But his trick—an unconscious one—is speaking generalities and using vague analogies while actually describing the only thing he really knows: tending his garden (as the garden man becomes Gardiner, Chance becomes the personification of television). His listeners supply the meaning and the profundity. Who could have planned it this way? Yet, Chauncey also seems on the verge of revelation. To pick up a thread from Nietzsche’s, The Use and Abuse of History, he writes how man looks at the herd and asks:

“Why do you look at me and not speak to me of your happiness? ” The beast wants to answer—“Because I always forget what I wished to say”; but he forgets this answer too, and is silent; and the man is left to wonder. (5)

While trying not to tread into the tracks of the liberal political stance of early television critiques like A Face in the Crowd, one cannot resist associating the political identity of Chauncey Gardiner with Ronald Reagan. Better, since the film appeared a year before Reagan’s election, Chauncey anticipates Reagan. We would not want to scare away conservatives who worship at Reagan’s altar; it should be understood that we might imagine Reagan being as innocent as Chauncey with the flair to communicate” with his audience. The times demanded Reagan’s appearance: a hollow politics filled with positive thinking bombast, sold to the public with the right one-liners and captions, reality locked up and made what Reagan’s White House wanted it to be. Not just Doublespeak but the Reagan mastery of the story that the teller himself didn’t know was fact or fiction, or had blended the fact and fiction to create a better sounding reality for the United States. He couldn’t have done it without television and its ethos. The achievement of Bill Clinton, within this ethos, is that he has consciously become what Reagan naturally was, which has meant that a different game has been played in the 1990s, a more sophisticated game, best seen in the documentary, The War Room.

Chauncey Gardiner’s name was derived from Shirley MacLaine’s character mishearing him saying, “Chance the gardener.” His garden-wisdom that mesmerizes the public keynotes his naturalness, his absence of pretense and phoniness. However, the name “Chance” strikes more deeply into the universe cued by television. Whenever he watches television, he both apes what he watches (a practice hilariously followed in the real world when he is given the message for Rafael) and turns the channels away from what he watches. Everything catches his attention, but he cannot stay with anything for very long. A Benjy Compson jerkiness caused by unconscious responses to the images on the screen. The arbitrariness of what he watches might represent a model of a universe which itself is naturally arbitrary; Man, the natural animal Man, becomes that universe of un-meaning and senselessness. Being There’s ultimate satiric point might well be that what the world finds most profound, most insightful, becomes the gateway to an arbitrary society. No one will then be able to answer why study this or that or why observe this or that law. All has become chance. Our parents met by chance, as all parents met by chance, and what we are becomes the sum of a universe of chance happenings. All meaning dissolves within this universe of chance. Such logic devolves all life to chance. To an extent everything can be explained away—starting with the behavior of sociopaths. The society, the world, melts into a paradise of the indistinct.

What kind of people would allow that? Were Americans the perfect people to have developed and be devoted to television? Have certain movies commented on the phenomenon? What kind of threat did movies see television being? How did perceptions of that threat change over the last fifty years? And were other media prior to the television age as much of a threat as television seems to be now to our national consciousness?

Americans appear to have been bred and born to watch television. Our movies tell us this, even when the subject of the movie has nothing to do with television. A persistent theme, however, issues from movies: Americans’ growing isolation and loneliness. Without indulging in an extensive critique of the culture, we can venture more than guesswork regarding our quintessential characteristics, those very ones Americans are actually proud of, like inventiveness and self-reliance, individuality and freedom. Indeed, movies and television are two excellent examples of our technological expertise; another would be the car.

While television watching established an American mode of being separated from people while maintaining the illusion of community in the second half of the twentieth century, the car created a mobile version of separation in the first half. The car liberated families for personal and individual trips (hence, the illusion of interconnection) and became the symbol for individual and sexual autonomy. Robert Kolker, in A Cinema of Loneliness, writes how, in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), the car becomes a motif of clannishness as opposed to society/community. While not creating the social mode, the car facilitates an inclination that Americans have gladly heralded as the Modern Age. When the myth of the physical frontier waned in the early twentieth century, Americans inaugurated a series of interests, including cars, movies, planes, and Freud, to carry them to new frontiers of speed, height, dreams, and individual autonomy. Increasingly, the pace of life quickened, the payoffs of our inventions had to be greater, and the convulsions of change within society deepened.

It is important to realize that television did not create something ex nihilo but has exacerbated our dominant tendencies to the point of unraveling our culture. A seminal study of the increasingly autonomous American character is David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd. By using the typology: tradition-, inner- and other-directed, this book deftly shows the American sociological landscape of the mid-1940s. The aptness of its appearance at the dawn of the Television Age couldn’t be greater, especially in the detailed observance of the psyche of the television viewer through the ample descriptions of the other-directed individual.

I understand the dangers here. The other-directed type represents, to a large extent, Riesman’s great lament about contemporary society. Inherent in this type is social and political consequences that Riesman obviously finds repellent. The nascent conformist of the Fifties is here; mostly, there’s the liberal worry over the political consequences of the other-directed type becoming dominant. The United States had just defeat fascism in Europe and Asia, but essentially The Lonely Crowd depicts an America with a Fascist-leaning citizenry or, at the least, with a people ill-immunized against manipulative leaders. A film derived from his subsequent study, Faces in the Crowd, also targets charismatic celebratory, advertising, and a right-wing political agenda.

Despite claims that The Lonely Crowd was naive, optimistic, and skeptical in an article in Society, Riesman describes the American psyche of the late Forties aptly if not grandly. The type, in a sense, is incidental in regard to its absolute accuracy or the accuracy of Riesman’s prescience. In essence, he writes, “the other-directed type finds itself at home in America” (35) and “other-directedness is the dominant mode of insuring conformity” (36), the latter both a great source of apprehension for sociologists and social scientists then (cf. Society article) and the commonplace description of America until the Stormy Sixties. What singularly defines the moral atmosphere of the other-directed is that “contemporaries are the source of direction for the individual—either those known to him or those with whom he is indirectly acquainted, through friends, through the mass media” (italics in the original). The component of contemporary influences cannot not be overestimated nor seen entirely in the light of “keeping up with the Joneses” in a world greatly accelerated by techno-media interventions like television and, soon, the computer.

In effect, conformity is effected not by drilling or inculcating behavioral patterns (hence the impotence of moralists like Bill Bennett who believes he can resurrect the inner-directed type) but by acceding “to the wishes and actions of others” (38). Being liked and approved of becomes the other-directed person’s “chief source of direction and chief area of sensitivity” (38). He/she “learns to respond to signals from a far wider circle than is constituted by the parents” (41). Amazingly, these analyses were made when movies, newspapers, and radio reigned supreme as the public mediators. There were few movies that stressed their own roles as deforming the public social fabric. There may have been abuses within the respective media—yellow journalism, gossip columnists á la Walter Winchell, staged productions or hyped events (the Scopes and Lindbergh kidnapping trial)—but the system seemed indomitable in a country on top of the world. The evolution of the critique of television, especially but not only by the movies (but definitely not by television itself), shows television’s greater complicity in fostering the latent values of other-directed culture to the point of social insatiability and moral nihilism.

Before connecting Riesman’s other-directed type to cinematic manifestations, it might help to flesh out other tendencies within the type:

- The type becomes a consumer trainee who’s able to make small qualitative differences signifying style and status; children join in the exchange of verdicts on products (and morals, a new kind of product that can be test-marketed by polling); and they develop great ability in expressing the proper preferences. (95-96)

- There’s insatiability for the amusements and agenda of popular culture.

- The other-directed child is trained to be sensitive to interpersonal relations.(124)

- Very importantly, the other-directed person has no self to escape from; no clear line between its production and its consumption; between adjusting to the group and serving private interest; between work and play.(185)

- This type is torn between the illusion that life should be easy and the half-buried feeling that it’s not easy for him (by the end of the millennium, this feeling has been fully buried).

- The other-directed person expects to be manipulated in an act which has its narcissistic tendencies: the pleasure of having attention lavished on me (how else can advertising and politics survive the revelation of all its secrets).

- Spectator apathy sets in when the glamorous objects are adored.

The process of other-direction also can be seen in Being There. An uncertain public1 and dimwit body politic cannot discern Chauncey’s empty phrases from real wisdom. They interpret his utterings as wise as long as the wisdom confirms their view of the world. Potentially, the Reaganite or Clintonista could fit into this category easily. Chance becomes a glamorous object—celebrity, par excellence, but more so their narcissistic reflection of themselves. At the film’s end Chance’s walking on water signals us that it won’t be long before his Christ-like qualities will be certified by the lonely and vacuous crowd.

To further legitimize Riesman’s typology, it should be noted that the other-directed individual bears strong resemblance to Ortega y Gasset’s “mass-man” as delimited in The Revolt of the Masses. The mass-man is a presumptive creature and believes that his world has been produced by nature (Ortega, 59). He does not realize that he has inherited only the techniques of modern life and not the spirit that created those techniques. Unaware of the ephemeral nature of this inheritance, he couldn’t care less. Curiously, there develops ingratitude toward those things that made existence easy for him (in other words, short-temperedness toward the technical means when those means don’t produce the desired results quickly enough). Importantly, the triumph over ancient barriers results in a free expansion of his vital desires: “By reason of removal of all external restraint, all clashing with other things, he comes actually to believe that he is the only one that exists, and gets used to not considering others, especially not considering them superior to oneself” (Ortega, 59). This shut up soul results from the opening out his world and is the very obliteration of the average soul that the revolt of the masses consists (Ortega, 68). Other qualities include 1) a spoiled-child psychology; 2) a life lacking any purpose; 3) a lack of romance in dealing with women; 4) a tendency to crush everything individual, select or excellent beneath him.

What Ortega describes as the elite or select minorities, it seems as if he were describing Riesman’s inner-directed type. In fact, The Revolt of the Masses, on one level, dramatizes the transition from the select man to a mass-man in Europe after World War I which he feels had led to the start of Fascist movements and nation-states (Ortega, 120).2 Riesman detects a parallel trend in Post-World War II America, and many of the differences in the description of this type comes partly from the geo-political area and partly from the difference in professions: Ortega’s a philosopher (Revolt is a work of philosophy), Riesman a sociologist. The similarities also underline Riesman’s fear of the right wing tendencies of his other-directed man (refracted into the political stance of the movie A Face in the Crowd). Television, as the perfect tool of the other-directed man, becomes a womb for fascist tendencies. Taking McLuhan’s dictum to a political extreme, we would say that the message of the television medium is the one most agreeable to the mass-man/other-directed man’s sensibilities. American resistance to the dominance of the mass-man has been always fragile. Our democratic ideology worships at the altar of the masses while trying to keep the masses from leaving the temple, so to speak. “Leaving the temple,” meaning: discovering a world whence their desires could be sated and unleashing this group and its values upon the world outside. Television did not cause the balance to tilt so much as once the tilting began television weighed in heavily on the masses side. The balance has been swept away; the masses don’t want to return to the temple.

Nowhere does the other-directed type express himself better than through the characterization of Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1982). Being There embraces the moral and intellectual consequences of television’s presence, and in this regard does not mortally offend a movie audience weaned on television. While the character of Chance embodies something horrible, it’s horrible at a distance through the satiric mode. And that’s where Being There bags its audience, implicating us like those in the film dealing with Chance because we think we “understand” and can master him/television. Swift operates the same way by the end of Gulliver’s Travels by making us identify with Gulliver’s disgust for the human race. Likewise, Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove has the audience laughing through the tale of the world being annihilated. Their high rank as satire depended on the audience separating itself from “the problem.” The King of Comedy’s Rupert Pupkin doesn’t allow us to distance ourselves. Director Martin Scorcese dramatizes the ugly side of the television ethos (we weren’t on the ugly side yet with Being There): people obsessed by the glamour of television and, consequently, equating this glamour with “meaning” or meaningfulness for their lives and trying to become a part of this glamour world.

Rupert Pupkin trying to become part of the TV glamour world. The King of Comedy (Embassy/Fox, 1982).

Upon viewing the film at a suburban theater, only ten people in the audience, I sensed immediately why it would be a box-office flop. Rupert Pupkin made me feel awful about myself. Being There’s satiric grounding provided an escape hatch for individual culpability (a movie like Wag the Dog provides the same escape for the audience; however, unlike for Being There, Wag’s did so because its satiric project finally collapsed upon itself). The King of Comedy emphasizes less the comedic aspect of Rupert’s obsession than how our own inclinations match Rupert’s. Being There also sported a tour de force performance by Peter Sellers, whereas Robert DeNiro’s Rupert couldn’t attract the usual DeNiro crowd partly because as “DeNiro” he was not recognizable. No matter how superior we feel to Rupert, no matter how we might convince ourselves that the celebrity mythology doesn’t affect us, traces of our base desires are mirrored by Rupert’s pursuits. When haven’t we thought of getting an autograph—Rupert has an album of them—or commented that so-and-so was in the restaurant or Wawa or wanted to be a guest on a talk show? His fantasies, be they the deal-cutting he does with Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) or sitting beside his Liza Minelli cutout in his basement, are not farfetched for many who grew up in the days of the Jack Paar, Johnny Carson, and Merv Griffin Shows. Not farfetched either for a generation of children who had not only watched The Mickey Mouse Club but also dreamed they would become part of that special television community. When Rupert plays out his parts, these fantasies metamorphose into realities, and we become sickened with an awareness of the decrepitude and vacuity of our own desires.

Rupert is a second-generation other-directed type, no longer seeking approval from keeping up with the Joneses. Pretensions of class-consciousness or rising in class status is no object for him; he wants approval on another plane, an approval which in a bizarre way is a kind of love which will make him feel alive, alive in the only way he—as an other-directed/mass-man—understands love: through applause with a laugh track. Riesman seems to have him in mind when writing: “The other-directed child, however, faces not only the requirement that he make good but also the problem of defining what making good means” (Riesman, 66). Making good for Rupert means getting on television and delivering an autobiographical routine to a nationwide audience. Why not? The television ethos in its purest form will endow a culture of definition based on ratings. And Ortega defines his mass-man type as one who’s impressed by large numbers. Such approval transferred to the celebrity culture (started before television) makes sense and seems great until the approval degenerates (cultivating a new form of life: analysts of mass approval given and withheld) and the ghastly prospect of celebrity death sickens but interests all (“what ever happened to the person who. . . ”). Riesman continues:

He finds that both the definition and evaluation of himself depend on the company he keeps [Rupert’s imaginative talkshow audience]: first, on his schoolmates and teachers; later, on peers and superiors. But perhaps the company he keeps is itself at fault? One can then shop for other preferred companies in the mass circulation media [my italics]. (Riesman, 66)

We only get to hear Rupert’s mother, yelling downstairs at him and interrupting his entertainment fantasies. A call to reality, maybe, or just an annoyance from that world in which Rupert knows he’ll never be much of anything. A true twist to Ortega’s idea of the mass-man, who sees bigness in his smallness. Rupert’s attempt at limited stardom, his “fifteen minutes” of fame, does not delude him that he’s talented. The film goes to great length to show that HE WANTS TO BE ON THE SHOW and has little interest in a showbiz career. He knows he’s not talented enough to make a career as a comedian. His routine represents the crowbar to break into the house of fame (afterward, when he’s finally captured, we are privileged to his newest illusion: nationwide fame from having kidnapped Jerry Langford and being given his own television show). Riesman explores the development of the type growing up and we partially glimpse the child-mind of Rupert Pupkin:

Approval itself, irrespective of content, becomes almost the only unequivocal good in this situation: one makes good when one is approved of. Thus all power, not merely some power, is in the hands of the actual or imaginary approving group, and the child learns from his parents’ reactions to him that nothing in his character, no inheritance of name or talent, no work he has done is valued for itself but only for its effect on others. (Riesman, 66)

Hence, the tremendous importance of Rupert’s routine. The autobiography of the mass-man. A sickening tale of (apparent) rejection by parents, peers, and teachers. An unlovable child or child who, for unclear reasons, perceived a world that didn’t approve of him.3 His “act” is, on one level, his revenge against an unfair existence (the mass-man stuck in a child’s psychology); he believes that the fame (a distorted form of approval) he garners from his kidnapping escapade will impress all those past acquaintances who believed he couldn’t get this kind of recognition. And many people will be convinced by his television appearance, like the women from his high school whom he had taken to Jerry’s house. The schmuck’s not so much of a schmuck if he could get a gig on the Jerry Langford Show. And can we not admit that we might have the same response, just as we might have had our celebrity appetite wetted occasionally?

You're talking to me? Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (Columbia, 1976).

To some, Rupert might seem more than the logical extension of the mass/other-directed man. In Robert Kolker’s A Cinema of Loneliness, the lineage of Rupert’s character is traced to earlier Scorcese creations in Taxi Driver and Raging Bull (Kolker, 209). Indeed, Travis Bickle is a more violent version of Rupert Pupkin. One can’t help noting the similar endings of the two movies whence both characters are elevated to a form of hero or celebrity status. Travis shoots the pimp and saves the child prostitute and becomes a savior according to the newspapers. The movie audience recognizes the antagonism between the real and the media version of Travis. With Rupert, we’re allowed no distance further averting us from wanting to have this version of ourselves imposed on us—in a way, Scorcese insists on our identification with Rupert as forcefully as Rupert imposes his fantasies on Jerry Langford and the rest of the world. Because we’re not certain whether Rupert at the end has a bestseller and a top-rated television show, it’s our misfortune to see the satiric thrust pierce our sternum.4 And if we relate Travis and Rupert here, it’s a small step to giving Rupert greater filmic lineage. Kolker and others remind us that Taxi Driver bears strong resemblance to The Searchers, Travis saving Jodie Foster as Ethan Edwards did Natalie Wood. It seems more perverted to link Travis Bickle, the quintessential asshole (his looks much like a greeting card picturing the same), to America’s all-time movie star and everything he represents. Yet the America he and John Ford were trying to save, an inner-directed one with community snugness, has essentially crumbled nearly at the same historical moment that they were representing it in film. Many of the contradictions in the John Wayne mythology of the lone-wolf individual and of American fair play have been described in Garry Wills’ recent book; its relevance here is two-fold. First, the Wayne myth was absolutely centered in his movie roles and persona, a creation of the media par excellence, so excellent the creation that the amalgam of the real and movie man in the public’s imagination remains seamless, his popularity for many people the proof of his greatness. Second, a generation or two later, the NEW seamlessness presents Rupert Pupkin. Only the question has been reduced from the Wayne-ian “is he a real hero” to a Pupkin-ian “is he a real celebrity? ”Rupert’s personal void becomes our moral vacuum. Ethan was turned out and unleashed upon the frontier. Travis took refuge in the taxi; Rupert, in television. How much further inward can these types recoil before disintegrating? Celebrity has become the paramount source of contemporary isolation, the best expression of a lonely culture that completely reveals itself shamelessly, groping for an approval which they know won’t really come or that they deserve, but where the spectacle of oneself becomes the ultimate rationale.

Works Cited

Kolker, Robert. The Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Kubrick, Scorcese, Spielberg, Altman, Second Edition, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Use and Abuse of History, translated by Adrian Collins, Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1957.

Ortega y Gasset, Jose. The Revolt of the Masses, translated by Anonymous, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1957.

Reisman, David, et al. The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character, Abridged edition, New York: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1953.

Wills, Gary. John Wayne’s America: The Politics of Celebrity, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Footnotes

1The film cleverly objectifies the social confusion in its own inability to distinguish whether the realtors are married to one another or the persons we first see them with in the bedrooms.

2 cf. Treason of the Clercs by Julien Benda, which describes the same phenomenon of elites declining their duty to lead and rule. Here, the accusations of conscious betrayal are strong and remind one of a similar view Oliver Stone takes toward television in Natural Born Killers.

3 The assertion of self-esteem stylists in education, psychology, especially, but everywhere else too, have made approval the standard by which children should be raised. Or better, not to give approval apparently damages the child’s estimate of his/herself, and this low “rating” will activate itself into poor performance later. Riesman deals extensively with the generation of other-directed types from households which, uncertain how to raise children, take the line of least resistance with them and relaxing all criticism and much of the discipline. The child cannot help but base the rest of his/her existence on how society approves it. Thus their sole motivation to work, morality, and truth is approval (not unlike the standards of Bill Clinton on the personal and political fronts).

4 In a sense events have caught up to the film. Convicted Watergate conspirator G. Gordon Liddy enjoys a career as a nationally syndicated radio host. And an ex-mayor, Jerry Springer, created a show for the Rupert Pupkins of the world.