This text has been submitted as an original contribution to cinetext on June 13, 2004.

More than This : Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation

|

|

by Samara Allsop |

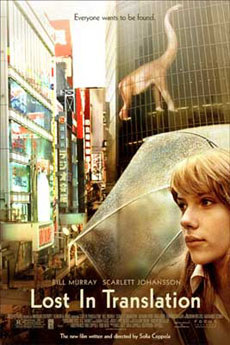

Sofia Coppola's (2003) Lost in Translation delves into the transitory nature of human life, analysing both the existence and non-existence of relationships and meanings that have the innate ability to transform and change the future direction of a person's perseity. Lost in Translation manages to capture the essence of human emotional fragility, the exquisiteness made all the more sweeter and poignant as it is often fleeting and as such impermanent. Coppola has managed to capture the vulnerability and strength of human interactions, ill-fated though they may often seem, they inevitably make an indelible impression that is long lasting and whose effects are far reaching.

The synopsis for the film is quite a simple one, it is at it's most basic, a romantic comedy where the two central protagonists relationship thrives not on sexual energy, but on the camaraderie and friendship they afford each other while 'alone' in a foreign city. The immediate alienation and the dislocating environment could have provided an ideal backdrop for a 'holiday' romance, evident within countless plots realised throughout cinema. Coppola however, chose not to follow this path, instead she focuses on the central characters sharing an awkward romance, spurned on by both their loneliness and the infrequent [for Harris] anonymity afford by their visit to another country where their shared 'otherness'[1] becomes a starting point on which to build a friendship. The central protagonist's are aligned to each other-in terms of nationality, socio-economic status and characterization—by their difference to the world around them. In other words Japan, the envisioned 'orient', frames them and as such defines their relationship to each other and themselves.

Bob Harris (played by Bill Murray) is in Toyko, Japan, to shoot commercials for Suntory Whisky. The two million dollars that he will earn is enough for him to retire on, his travel weary face and demeanour indicates that he is already tired of making the obligatory media appearance's that stardom requires. Also in Tokyo is Charlotte (played by the statuesque Scarlett Johansson), a young photographers wife. Unlike Harris, Charlotte has no specific reason for being there other then to accompany her photographer husband John (Giovanni Ribisi) who drifts in and out of the film like a mirage of productivity. His industrious work schedule is equal to his wife's lackadaisical approach to her life and while her husband remains absent she remains at best apathetic. Charlotte's attitude (or lack thereof) stems from her unwillingness to enter into the next phase of adulthood by choosing herself a career and hence a life direction. A graduand of the prestigious Yale University in the States (where she undertook a philosophy major) she precariously floats between the distractions of early adulthood and the demands of corporate adulthood—something she invariably shares with Harris who appears to be entering a mid-life crisis.

Charlotte and Bob at the hotel bar. Lost In Translation (American Zoetrope / Constantin / Universal, 2003)

As such, both characters are driven towards each other in an attempt to locate themselves. Together they are alone in what could arguably be called one of the busiest cities in the world, left to ponder over 'the meaning of life' in the darkest hours of the night. Their rendezvous takes place in and around the luxury Park Hyatt hotel, a gilded cage for wealthy travellers and business people. It becomes increasingly obvious that the confines of the hotel reflects the tight dimensions of their own lives. Thus comfort is often drawn from solitary moments, the act of remembering and of knowing and being aware that the other is in another part of the hotel is sometimes enough, and while the characters are physically alone with their thoughts they are drawn closer together in memory. The inner sanctum of the Park Hyatt acts as a cocoon from the outside world (and all the emotional turmoil and uncertainty associated with it) and they are able to reflect somewhat on their own happiness. Their awkward romance is never physically consummated however the emotional attachment becomes apparent as each day passes and each exchange becomes more personal and intertwined. It is as if Coppola has woven a silken thread that fastens the specific and separate moments of the characters infatuation and self-discovery together-the end result being the fabric of the film.

Coppla herself commented that "...she was inspired by the dynamic between Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in Howard Hawks classic 1946 noir The Big Sleep..." [2]. Indeed Lost in Translation has a slightly retro feel to it (and perhaps in some places pays homage to this) and this emphasised greatly during the '..for relaxing times, make it Suntory times...'shoots with Harris and the Japanese Suntory team. Harris is forced to become a debonair 1950/60's personality, edged on by the director played by Yutaka Tadokoro (who himself is a Japanese rock star) shouting at him to be more like Frank Sinatra or Roger Moore. He is told to convey meaning through his image, to express himself with 'intensity'. The director is aiming at an image that can transcend cultural boundaries. The lack of understanding between the director and Harris is one based on linguistic difference not cultural difference. Indeed Tadokoro presents Harris with a smorgasbord of American culture, from the infamous 'rat pack' to James Bond in an effort to make him feel more at ease during the shoot (Harris is after all the only one who cannot speak Japanese in this scene). Lost in Translation has suffered somewhat by claims of racial vilification, that there is an idea that "...hilarity is rooted entirely in the "otherness" of the Japanese people. We laugh at them, not with them...[hence this] is why the film is accused of being racist."[3]. One could not argue that the film did not stereotype certain Japanese characters, however if one was to deal with the film subjectively then one would need to acknowledge the fact that it makes fun of all the characters within it, not just the Japanese, and the majority of the comedic relief comes at Harris's expense, not the Japanese characters.

Bob makes it "Suntory times". Lost In Translation (American Zoetrope / Constantin / Universal, 2003)

It is Harris, and to an extent Charlotte, that cannot overcome the language barrier, nor does it seem they want to. Harris and Charlotte are so 'lost' amongst the linguistic misunderstandings and misappropriation of such linguistic difference that they fail to appreciate just how accommodating the Japanese character's are. These characters all make some sort of attempt at communicating with Harris in English (or at the worst of times in broken English) however apart from the occasional 'konnichiwa' he refuses to even try to speak Japanese. Charlotte is just as distracted. A prime example of this linguistic imperialism is the 'rip my stocking' scene in Harris's hotel room. The misunderstanding stems from Bob's inability to comprehend what the Prime Fantasy Woman (played by Nao Asuka) is saying, not the other way around. It is only when her frustration at Harris has reached it's limit does he start to comprehend what she is saying. In this sense then, Lost in Translation is making a statement about cultural identity and norms, namely that 'Otherness' does not only have to apply to the culturally marginalised (as is often argued about 'orientalism' and the idea of 'other') but rather that it is an ambiguous term and by it's very definition can be applied to any traveller anywhere. The 'Other' can "...include a battery of desires, repressions, investments and projections."[4] and Coppola has expressed this with all the character's within the film. For example, the character of Kelly (Anna Farris) is so hyperactive, so unreal and so overtly American that one can really only describe her as a hyper-real construct of a perceived American personality—just as the character of Charlie Brown is the equivalent Japanese version. Hence one can argue that Lost in Translation aims at a kind of self reflection, not only for the character's but for the audience too.

It is interesting that a film with the title 'Lost in Translation' does not rely on heavy dialogue to impart a feeling and to help initiate a scene or even to show communication between Harris and Charlotte. Words seem to be somewhat worthless. That which is felt is often conveyed more powerfully in actions (and images) than words, and it is precisely this idea that Coppola is so talented at exploiting. Consider the last scenes of the film. The inaudible words whispered so tenderly into the ears of Charlotte has captured more audience interest than it would have if we had we been privy to the conversation. The fact that one is unable to arrive at a definite decision regarding it's content speaks volumes about the power of images in contrast to superficial conversation. If, as an experiment you type into the Google search engine the words "lost in translation whisper", you will be confronted with pages and pages of hyperlinks to sites devoted to understanding, philosophising, theorising and debating what was said by Harris to Charlotte. The image of Harris whispering to a wide eyed and tearful Charlotte appeals to most viewers who are content to ad-lib the ending in favour of the constructed romance diegesis, not wanting the two characters to part without some sort of memorable utterance. Indeed what was said was most certainly 'lost' however it is 'lost' within the audience's own idealised ending. The film's emphatic climax is the inaudible whisper however it also places emphasis on the fact that the transgression from friend to lover is never fully realised. Perhaps this is what is so appealing to contemporary audiences who are often used to graphic representations of sexual conduct.

Tender whisper. Lost In Translation (American Zoetrope / Constantin / Universal, 2003).

Lost in Translation in this instance can be compared to Wong Kar Wai's (2000) In the Mood for Love, and similarities between Coppola and Wong can be drawn. Both Coppola and Wong place more emphasis on what could be, on the hidden desire that drives two characters to new emotional strengths and weaknesses. Elizabeth Wright, a film critic, wrote that Wong's style is most evident in:

"...the characters repression of desire [and] that [is where] emotion can most be felt. It is about what not is said or acted upon the screen, that which the audience is aware of but not shown. There is a three dimensional depth that exists behind every character and every door" [5]

This sentiment, written primarily about Wong's In the Mood for Love aptly sums up the repressed feelings of Harris and Charlotte in Lost in Translation and best describes Coppola's film style. Both films are similar in their approach to the representation of emotion, self and relationships, often relying more on the misc-en-scene of a scene then actual spoken word to convey feeling. Coppla's success as a new director owes much to her talent in capturing the mundane and ordinary and turning it into something exquisite and valuable. She is able to capture the essence of a moment and presents it as such, not relying on fan fare or special effects to enhance it. Each scene is like a postcard or photograph of an instant memory in the moments shared between Harris and Charlotte. The solitary moments that each character experiences are also framed this way. Shots of Charlotte waking up, going to sleep and gazing out of the window are carefully constructed so that image is everything and the spoken word is inconsequential. Even John, her husband is absent. All that he has left behind for her are polaroids of themselves.

Charlotte gazing out of the window. Lost In Translation (American Zoetrope / Constantin / Universal, 2003).

Being a photographer, Coppola has managed to create stylized scenes that all manage to have an air of stillness about them. This exists in even the most busiest of scenes such as the amusement parlour and the night club. Indeed Coppola herself commented that she based her construction of the film around how photographs would look like [6]. For example the simple act of Harris looking out a taxi window into the reflected neon light landscape turns into a quiet moment of contemplation, an obvious valued occasion in a usually busy life. The audience is drawn to the image as it is both chaotic (flickering neon lights, motion of taxi) as it is beautiful. But it is also somehow peaceful, the moments when the lights reflect upon Harris skin and illuminates his features provides a second of perfect stillness. This is also true of the scene that shows Charlotte walking amongst the gardens at the Shinto shrine in Kyoto. At having come upon a traditional Japanese wedding Charlotte can only stare at the created image of outstanding beauty until she moves on—to the next stylised scene. Every part of those particular scenes are almost perfect and Coppola has, in the true meaning of the term, created moving pictures. Lost in Translation succeeds in drawing the audience towards the central protagonists as the images are constructed to focus on Harris and Charlotte almost exclusively—even in the face of visual and auditory interference—the karaoke scenes are a case in point. It is this intimacy between audience and character that works well for Coppola. It is an intimacy unbound by language and the film cleverly manages to capture the essence of each moment spent together.

It is often harder to write about something that you admire, perhaps because on closer inspection flaws may become evident and the allure of the original threatens to pale slightly. This however is not the case with Lost in Translation. The beauty of the film and the meanings that one can derive from it start to surface with more magnitude after the credits role and you are left pondering upon the meaning of the images left behind in your memory. Sofia Coppola has managed to present the world with a simple romantic comedy, yet within this framework she has touched upon important subjects such as identity and cultural connectivity. Lost in Translation does everything but living up to it's title.

References and Endnotes:

[1] Said, Edwa W. (1979), Orientalism, Vintage, New York.

Edward Said's famous theory of 'the other' is realised in most socio-anthropological and historical writings and this trend has also influenced film writers in critiquing cinema. A good web source of knowledge concerning Said and his various writings is The Edward Said Archives http://www.edwardsaid.org

[2] Thompson, Anne (2003), 'Tokyo Story', Filmmaker Magazine, Fall, 2003 Also Found Online: http://www.filmmakermagazine.com/fall2003/features/tokyo_story.html

[3]E. Koohan Paik 'Is "Lost in Translation" Racist?' http://www.asianamericanfilm.com/archives/000602.html

[4] Said, Edward W. (1993) Culture and Imperialism. Alfred Knopf, New York. Cited in Rosen, Steven (2000), 'Japan as Other: Orientalism and Cultural Conflict', in Journal of Intercultural Communication, November, Issue 4. Also Found Online: http://www.immi.se/intercultural/nr4/rosen.htm

[5] Wright, Elizabeth (2001), 'The Cinema of Wong-Kar Wai: A Writing Game: Desire', compiled by Fiona,Villella (2001)'The Cinema of Wong-Kar Wai: A Writing Game', in Sensesofcinema http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/01/13/wong-symposium.html

[6] Mitchell, Wendy (2003), 'Sofia Coppola Talks About "Lost In Translation," Her Love Story That's Not "Nerdy"', IndieWire.com Available Online: http://www.indiewire.com/people/people_030923coppola.html

Lost in Translation Website: http://www.lost-in-translation.com